How Gardening Supports Kids' Mental Health: Building Emotional Resilience in the Garden

We often think of gardening in terms of what it produces: tomatoes, zucchini, fresh herbs for dinner. But for children, the garden may offer something even more valuable than vegetables. It offers a natural environment for building emotional resilience, reducing stress, and developing the social-emotional skills that help kids navigate an increasingly complex world.

The research on this connection has grown substantially in recent years, and the findings are encouraging. Regular time in the garden appears to support children's mental health in measurable ways, from reduced anxiety to improved mood to stronger coping skills.

For families in Santa Cruz County, where outdoor time is possible year-round and nature is never far away, gardens offer an accessible, low-cost way to support children's emotional wellbeing alongside their physical health.

The Nature Connection: Why Outdoor Time Matters for Kids' Minds

Before diving into gardening specifically, it helps to understand the broader context. Time spent in nature is consistently linked to better mental health outcomes in children, and gardening is one of the most accessible ways to provide that nature connection.

The reasons aren't fully understood, but researchers point to several factors. Natural environments reduce the sensory overload of modern life. Green spaces appear to lower cortisol (the stress hormone) and activate the parasympathetic nervous system, which governs rest and recovery. Being outdoors exposes children to sunlight, fresh air, and physical movement, all of which support mood regulation.

Gardening adds something beyond passive nature exposure. It provides purposeful activity, tangible goals, and the satisfaction of nurturing living things. This combination of nature contact and meaningful engagement appears especially powerful for emotional wellbeing.

What the Research Shows

The evidence linking gardening to mental health benefits spans ages and settings, from school garden programs to therapeutic horticulture to backyard growing.

A comprehensive meta-analysis of gardening interventions examined studies across age groups and found consistent patterns: people who garden show reductions in depression and anxiety, lower stress levels, and improved quality of life compared to non-gardeners. While much of this research focuses on adults, studies specifically examining children and youth show similar benefits.

Mayo Clinic Health System notes that gardening can reduce stress, improve mood, and provide physical activity benefits comparable to other moderate exercise. The combination of movement, outdoor time, and purposeful activity creates what researchers call a "multi-modal" intervention, one that works through several pathways simultaneously.

Colorado State University Extension's work on horticultural therapy describes how garden programs support mental health through reduced stress, improved mood, and increased self-esteem. These benefits appear in both clinical populations (children with anxiety disorders, ADHD, or trauma histories) and in general populations of kids without diagnosed conditions.

Research from the University of Florida Extension specifically examines youth populations and confirms that gardening helps reduce stress and anxiety in young people. The effects are particularly notable for children who may not thrive in traditional indoor, sedentary learning environments.

How Gardening Supports Emotional Regulation

Beyond general stress reduction, gardening appears to help children develop specific emotional regulation skills. These are the abilities to recognize, understand, and manage emotions, skills that serve as foundations for mental health throughout life.

Predictable routines create security. Gardens operate on rhythms: daily watering, weekly weeding, seasonal planting and harvesting. For children (especially those who struggle with transitions or uncertainty), these predictable routines provide structure that supports emotional stability. A child who is anxious about an upcoming test can still count on the garden needing water this evening.

Sensory experiences ground and calm. Touching soil, smelling herbs, listening to birds, watching bees move between flowers: gardens provide rich sensory input that can help children shift out of anxious or agitated states. Occupational therapists and mental health professionals use similar sensory strategies in clinical settings; gardens offer them naturally.

Delayed gratification builds patience. In a world of instant everything, gardens insist on their own timeline. Seeds take days to germinate. Tomatoes take months to ripen. Learning to wait, to trust the process, to find satisfaction in gradual progress, these are emotional skills that transfer well beyond the garden.

Caring for living things builds empathy and responsibility. When a child is responsible for keeping plants alive, they practice attending to needs outside themselves. This outward focus can be especially valuable for children prone to rumination or self-focused anxiety.

"Failure" becomes learning. Plants die. Pests arrive. Harvests disappoint. Gardens provide countless opportunities to experience setbacks in low-stakes contexts and practice responding constructively. A child who learns to shrug off a failed tomato crop and try again next season is building resilience that serves them in harder situations.

Social-Emotional Learning in the Garden

School-based research has examined how gardens support the specific competencies that educators call "social-emotional learning" (SEL): self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making.

Cornell University's Garden-Based Learning program summarizes research showing that youth garden programs support cooperation, responsibility, empathy, and sense of belonging. Gardens naturally require collaboration (sharing tools, dividing tasks, working toward common goals) and provide authentic contexts for practicing social skills.

KidsGardening's review of social-emotional learning research highlights how gardens give children chances to practice kindness, teamwork, and self-regulation in real-world contexts. Unlike contrived classroom exercises, garden challenges are genuine: the bed really does need weeding, the water really is limited, the harvest really will be shared.

School counseling perspectives on garden programs describe gardens as tools for reducing stress and improving social-emotional growth among students. Counselors report that garden time can be especially valuable for children who struggle in traditional classroom settings or who need alternative contexts for building relationships with peers and adults.

KidStuff Counseling's perspective on gardening and mental health emphasizes the therapeutic potential of garden activities for children dealing with anxiety, depression, or difficult life circumstances. While not a replacement for professional treatment, gardening can be a meaningful complement to other mental health supports.

Garden Activities That Support Mental Health

Certain garden tasks align particularly well with emotional regulation and stress reduction. Understanding these connections can help you structure garden time to maximize wellbeing benefits.

| Activity | Emotional benefit | Why it works |

|---|---|---|

| Watering | Calming, grounding | Repetitive motion with sensory feedback (sound of water, cool mist) and an immediate visible effect |

| Weeding | Stress release, focus | Physical outlet for tension; requires attention that can quiet rumination; satisfying visible progress |

| Planting seeds | Hope, anticipation | Future-focused activity that counters hopelessness; tangible investment in tomorrow |

| Observing (pollinators, new growth) | Mindfulness, presence | Encourages slowing down and noticing; a natural mindfulness practice |

| Harvesting | Accomplishment, pride | Concrete evidence of success; celebratory feeling; tangible reward for patience |

| Sensory exploration (smelling herbs, touching textures) | Grounding, regulation | Activates the parasympathetic nervous system and shifts attention from internal worry to external sensation |

These benefits aren't automatic. A child who is rushed through garden tasks or pressured to perform won't experience the calming effects. The key is allowing enough time for the activity to become absorbing, keeping the atmosphere relaxed, and following the child's interests rather than imposing an agenda.

Building a Mental Health-Supportive Garden Routine

You don't need a formal program to capture gardening's mental health benefits. Simple, consistent routines work well for most families.

Make garden time predictable. A brief daily "garden check" can become a calming transition, something to count on between the chaos of school pickup and the demands of homework and dinner. Even five or ten minutes of watering and observing can shift a child's state.

Use multi-sensory engagement. Encourage children to touch, smell, listen, and look. "What do the tomato leaves smell like today?" "Can you hear any bees?" "How does the soil feel, wet or dry?" This sensory focus is a natural mindfulness practice that helps children become present rather than anxious.

Invite observation, not performance. Ask "What did you notice?" rather than "What did you accomplish?" Keep the focus on curiosity and connection rather than productivity or perfection. Gardens are one of the few spaces in children's lives where there's no grade, no score, no ranking.

Allow quiet. Gardens don't require constant conversation. Comfortable silence while working alongside each other can be deeply connecting. Don't feel pressure to fill every moment with teaching or discussion.

Follow difficult days with garden time. When your child has had a hard day at school, a friendship conflict, or a disappointment, consider offering garden time as a way to decompress. Physical activity, fresh air, and purposeful tasks can help process difficult emotions better than talking (or screens).

Create seasonal rituals. Planting the first seeds in spring, the summer tomato harvest, putting the garden to bed in fall: these seasonal markers become anchoring rituals that provide continuity and something to look forward to across the year.

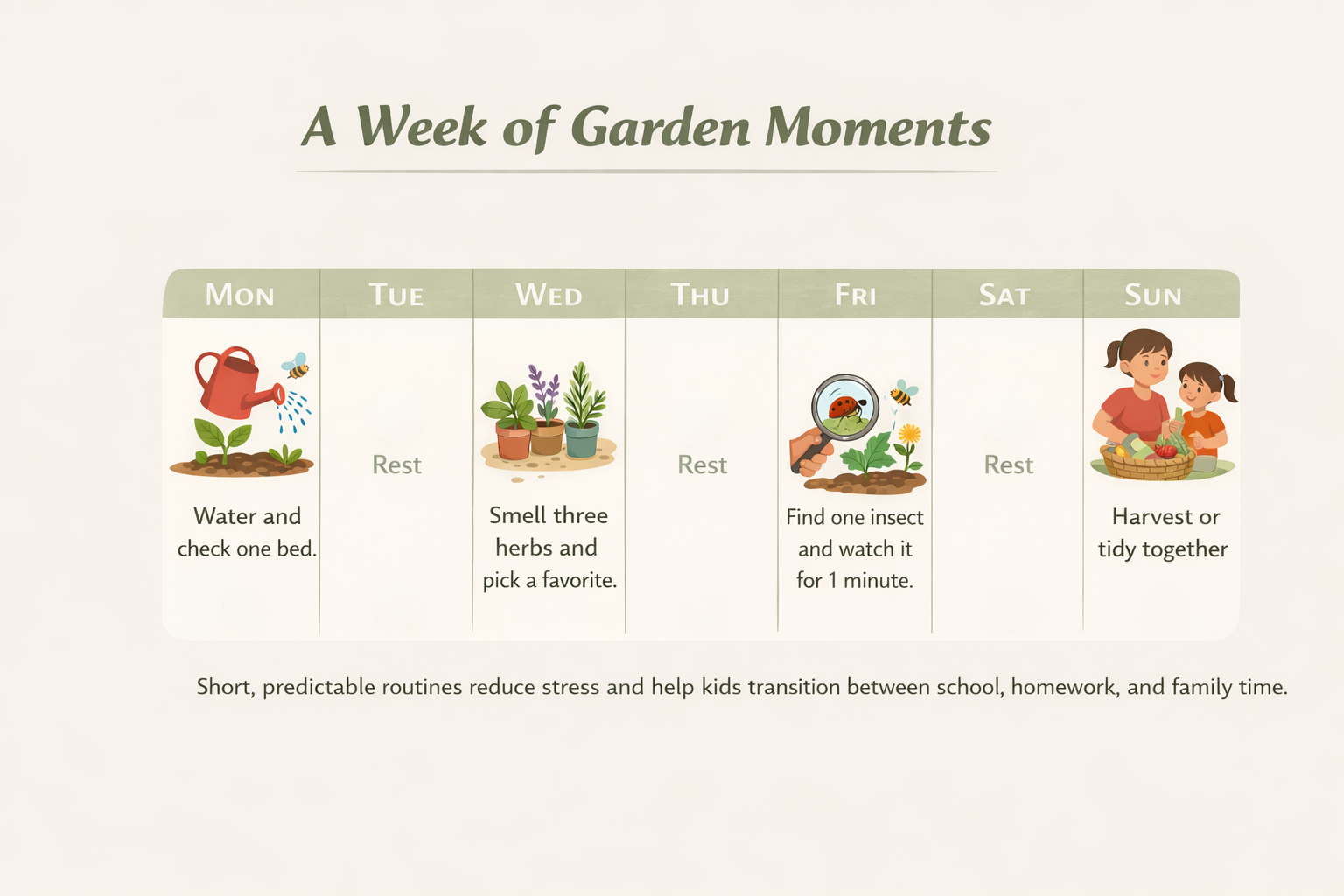

A Week of Garden Moments

You don't need hours of garden time to see benefits. Here's what a simple weekly rhythm might look like:

Monday: Quick watering and check-in after school. Notice what's changed since Friday. Five to ten minutes.

Wednesday: Slightly longer session. Weed one bed together, harvest anything ripe, smell three different herbs and pick a favorite. Fifteen to twenty minutes.

Friday: Observation time. Find one insect and watch it for a full minute. Look for new flowers or fruits. Talk about what you're looking forward to next week. Ten to fifteen minutes.

Weekend: More substantial garden time if desired. Planting, bed preparation, bigger projects. Or simply more relaxed versions of weekday activities. Duration flexible based on interest.

This rhythm provides regular contact without making gardening feel like another obligation. Adjust based on your family's schedule and your child's engagement level.

When Gardens Help Most

While gardening benefits most children, certain kids may find garden time especially valuable:

Children prone to anxiety. The predictability, sensory grounding, and present-focus of gardening can help anxious children shift out of worry loops. Gardens provide something concrete to do with nervous energy.

Kids who struggle with traditional learning environments. Children who have difficulty sitting still, focusing in classrooms, or learning through reading and listening often thrive in hands-on outdoor settings. Gardens offer an alternative context where different strengths emerge.

Children processing difficult experiences. Grief, family transitions, moving to a new home: gardens can provide continuity and a sense of control during times when much feels uncertain. Caring for plants offers something stable to hold onto.

Kids with sensory processing differences. For children who are over- or under-responsive to sensory input, gardens can be either calming (for those easily overwhelmed) or stimulating (for those who seek sensory input). The outdoor setting provides more space to regulate than indoor environments.

Children who benefit from physical activity. Some kids regulate their emotions best through movement. Digging, hauling soil, pushing wheelbarrows, and other active garden tasks provide physical outlets that support emotional regulation.

Important Caveats

While the research on gardening and mental health is encouraging, it's important to maintain perspective.

Gardening is not therapy. For children with significant mental health concerns (clinical anxiety, depression, trauma-related symptoms, or other diagnosed conditions), gardening is a complement to professional care, not a substitute for it. If your child is struggling, please work with qualified mental health providers.

Not every child will love gardening. Some kids simply aren't interested, and that's okay. Forcing garden time when a child clearly doesn't want to be there undermines the very benefits you're trying to provide. Look for the nature-based activities your particular child enjoys, whether that's gardening, hiking, beach time, or something else entirely.

The adult's state matters. If you're stressed, impatient, or treating garden time as another task to check off, children will pick up on that energy. The mental health benefits flow from the quality of the experience, not just the activity itself. If you're not in a good headspace, it's okay to skip garden time or let your child work independently.

Benefits accumulate gradually. Don't expect a single garden session to transform your child's mood or anxiety levels. The research shows effects over weeks and months of regular engagement. Think of gardening as one healthy habit among many, not a quick fix.

Local Resources for Garden-Based Wellbeing

Santa Cruz County offers several resources for families interested in deepening the connection between gardening and mental health.

School garden programs at many local schools recognize the social-emotional benefits of garden time. If your child's school has a garden, ask about how it's used for more than just science curriculum. Many programs explicitly incorporate social-emotional learning goals.

UCSC Arboretum and Botanic Garden provides peaceful outdoor spaces that can serve similar purposes even without hands-on gardening. Sometimes just being in a cultivated natural space supports wellbeing.

Local nature therapy and ecotherapy practitioners offer more structured approaches for children who might benefit from professional support combined with nature-based activities. Search for "nature therapy Santa Cruz" or ask your child's pediatrician or therapist for referrals.

Master Gardener programs through UC Cooperative Extension offer gardening education that can help you build confidence in creating and maintaining a garden space. More gardening knowledge often translates to more relaxed, enjoyable garden time with kids.

Community gardens in several Santa Cruz County locations provide garden space for families without yard access. The social aspect of community gardens adds another layer of potential benefit, as children interact with other gardeners and experience a sense of belonging to a larger community.

Frequently Asked Questions About Gardening and Kids' Mental Health

How much garden time do kids need to see mental health benefits?

Research on garden programs typically involves regular sessions over several months, but home gardening doesn't require a specific dose. Consistency matters more than duration. Brief daily contact (even five to ten minutes of watering and observing) appears to be more beneficial than occasional long sessions. The goal is making garden time a normal, expected part of life rather than a special event that requires planning.

Can gardening help with ADHD symptoms?

Some research suggests outdoor time and hands-on activities may help children with ADHD focus and regulate their energy. Gardens provide physical activity, novel stimulation, and tasks with immediate feedback, all of which can work well for ADHD brains. However, gardening is not a treatment for ADHD and shouldn't replace medical care or educational accommodations. Think of it as one supportive element in a broader approach.

My child seems more frustrated than calm in the garden. What should I change?

Several things might help. First, check your own energy. Are you relaxed or trying to accomplish too much? Second, let your child lead more. Frustration often comes from feeling controlled or failing to meet expectations. Third, focus on exploration rather than production. "Let's see what's happening" feels different than "We need to weed this bed." Finally, some children genuinely don't enjoy gardening, and that's okay. Not every activity suits every child.

Is there an age when gardening is most beneficial for mental health?

The research shows benefits across age groups, from preschoolers to teenagers. Different ages may connect with different aspects: young children often love the sensory experience and the magic of seeds sprouting; older children may appreciate the responsibility and visible results of their work; teenagers sometimes find gardens to be a welcome break from screens and social pressures. Adapt your approach to your child's developmental stage and individual interests.

Can indoor plants provide similar benefits if we don't have outdoor space?

Indoor plants offer some of the same benefits (caring for living things, observing growth, sensory engagement with soil and leaves) on a smaller scale. They're not equivalent to outdoor gardening, which adds sunlight, fresh air, and more physical activity, but they're much better than nothing. Windowsill herb gardens, terrariums, or houseplant collections can support children's wellbeing even without outdoor space.

Should I use garden time as a consequence or reward?

Generally, no. Linking garden time to behavior ("You can garden after you finish homework" or "No garden time because you didn't clean your room") can undermine its emotional benefits by adding pressure and conditionality. Instead, try to make garden time a consistent, expected part of routine that happens regardless of other factors. The exception might be a child who genuinely asks for extra garden time as a preferred activity.

How do I know if my child's mental health needs more support than gardening can provide?

Signs that professional help may be needed include persistent sadness or irritability lasting more than a few weeks, significant anxiety that interferes with daily activities, withdrawal from friends or activities they used to enjoy, changes in sleep or appetite, talk of hopelessness or self-harm, or any sudden dramatic changes in behavior or mood. If you're concerned, consult your child's pediatrician or a mental health professional. Gardening supports wellbeing but doesn't treat mental illness.

Can gardening help children who have experienced trauma?

Gardens can be one component of trauma recovery, offering predictability, sensory grounding, and opportunities for nurturing living things. However, trauma requires professional treatment. If your child has experienced significant trauma, work with a qualified therapist who can guide appropriate activities, including whether and how to incorporate gardening. Some trauma therapists specifically integrate nature-based approaches into their practice.

Free Gardening with Kids Resources

Seasonal Planting Calendar — Plan your garden year so there's always something to plant, tend, and harvest, keeping the garden active and engaging across all seasons.

Know Your Microclimate Worksheet — Understanding your specific growing conditions helps you choose plants that thrive easily, reducing frustration and increasing the satisfaction of successful gardening.

Beginner Garden Setup Checklist — If you're just starting out, this guide helps you create a garden space that's manageable and rewarding rather than overwhelming.

Garden Troubleshooting Guide — When problems arise, having solutions at hand keeps garden time positive rather than frustrating.

Cultivating Calm, One Garden Session at a Time

Gardens won't solve all of childhood's challenges. They won't eliminate anxiety, cure depression, or replace the professional support that some children need. But they offer something valuable nonetheless: a natural, accessible, low-cost way to support emotional wellbeing through regular contact with growing things.

The benefits accumulate quietly, through hundreds of small moments. A child who learns that watering the garden helps them feel calmer after school. A teenager who discovers that weeding is a better outlet for frustration than scrolling social media. A family that creates shared rituals around planting and harvest that become touchstones across the years.

Here in Santa Cruz County, where mild weather makes outdoor time possible year-round, gardens can be a consistent presence through all of childhood's seasons: the challenging ones and the joyful ones, the anxious transitions and the settled routines.

Start with what you have. A few containers on a patio. A corner of the backyard. A plot in a community garden. The scale matters less than the consistency, and the harvest matters less than the process.

What you're growing, ultimately, is not just vegetables. You're growing resilience, presence, and calm. You're growing a relationship between your child and the natural world that can support them long after they've left your garden and made their own.